The 57th Venice Biennale [2], the world's oldest international exhibition of contemporary visual art, opens Saturday May 13 under the theme Viva arte viva, or "Long Live Living Art." Founded in 1895, this prestigious art show-of-shows is expected to attract over 100,000 visitors before it closes Nov. 26. On offer this year are the works of 120 artists from 51 nations. Many are quite young, and 103 of them have never before participated in a Biennale.

In addition, 86 countries, which include the newcomer nations Antigua and Barbuda, tiny Kiribati and Nigeria, have pavilions showing the work of their own artists. These national pavilions include, representing Italy, three artists Andreotta Calò, Cuoghi and Husny-Bey in what is described by the authoritative critic Achille Bonito Oliva as a "convivial aesthetic dialogue" and "an exclamation of joy and the affirmation of art as the biological breath of all mankind." Curator of the Italian pavilion is Cecilia Alemani, who says her intention is less to give a systematic vision of today's Italian art world, but "more about offering a different kind of experimental platform for artists–a space for taking risks and trying new approaches."

In the U.S. pavilion is the noted Mark Bradford of Los Angeles, whose work is described as embodying content via abstraction. To this end he utilizes mundane materials such as pickings from LA streets, from Home Depot and from hair salons. A special concern: marginalized people. His work–says his website–reflects "his longtime commitment to the inherently social nature of the material world we all inhabit... Bradford renews the traditions of abstract and materialist painting, demonstrating that freedom from socially presecribed representation is profoundly meaningful in the hands of a black artist. See >>> [3]

For Paolo Baratta, Biennale president since 2008, "The Biennale is a great institution. It operates in multiple areas, partly for historical reasons, beginning with a theater festival back in 1895, to which were added what were then the 'new visual arts.'" To the Venetian calendar the world's first cinema festival was added in 1932. Later architecture was given its own pavilion within the Biennale, beginning with the exhibition Strada Novissima by architect Paolo Portoghesi. Today the Biennale still includes architecture and cinema as well as visual art, but also a Dance Festival that opens June 23; Theater Festival, July 25; and Biennale Music Festival, Oct. 29. "Multidisciplinarity remains the strong point of the Biennale," says Baratta. "And, beyond the greater of lesser influx of people and glamour, all the activities we produce here are of equal importance for us."

Exhibition centerpiece is the vast Central Pavilion of the Gardens, whose curator is Christine Macel, chief curator of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. She is not a newcomer; in the past she curated both the French and Belgian pavilions. In selecting the artists to participate this year, Macel focused on the concept of otium, which she interprets not as not laziness, but "that moment of not working–of being available, of laborious inertia, of the work of the spirit, of tranquility, of the kind of inaction that gives birth to a work of art."

At a time of great world tension, she explains, "Today's art is a testimonial to the most previous part of humanity–[the need for] a perfect place for reflection and freedom, and an alternative to individualism and indifference." Photographs reflecting this otium theme, chosen by curator Macel, are by Croatian artist Mladen Stilinovic, who died almost one year ago. From his 1978 series called Artist at Work, several show the artist sound asleep on a cot.

While curator Macel has searched far and wide for brilliant newcomers to the world art scene, the works of a few world art stars are also on view. From the United Kingdom comes sculptor Phyllida Barlow, 73, whose huge stone shards jutting out from a wall at the six-room British Pavilion, and her outsized weird grey boulders and columns are actually frightening. She has called her exhibition Folly [4].

Among the most famous is Olafur Eliasson, 50, born in Copenhagen to parents from Iceland, and with studios in both Copenhagen and Berlin. For the Biennale, Eliasson is putting 40 refugees now living in Italy to work in an "artistic workshop," as he calls it, making lamps of Eliasson's design. In the end the lamps will be sold to help finance his project, which he has named Green Light. "It's a 'green light' in the sense of a traffic signal saying 'Go,' come forward, you are welcome," he said in an interview in Denmark with Italian journalist Antonella Barina. The goal is to "contribute to the insertion of a group of refugees into society."

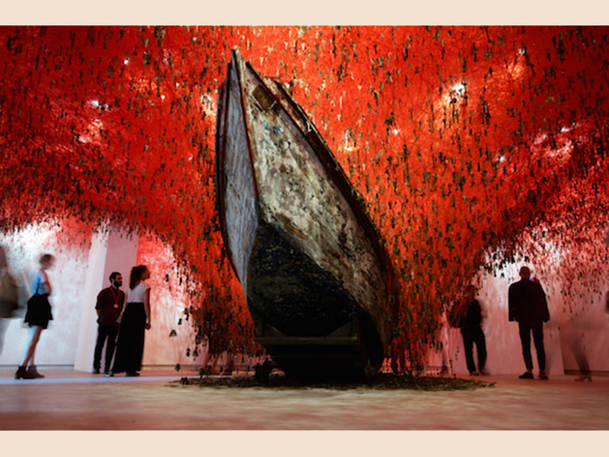

Not all the exhibitions are official. As a veteran of previous Biennali, this reporter can confirm what a thrill it is to be there and to see some of the side shows–to see the very first Vatican pavilion (none this year, however), the exhibition by Yoko Ono (which ended with morning coffee with her), and, best of all, the incredible and deeply moving installations by contemporary artist Ai Weiwei, which were half-size models of his imprisonment in China.

Source URL: http://440468.6bgr9ubv.asia/magazine/focus/art-culture/article/viva-arte-viva-57th-venice-biennale

Links

[1] http://440468.6bgr9ubv.asia/files/vivaartevivabiennalevenicejpg

[2] http://www.labiennale.org/en/art/exhibition/

[3] http://www.markbradfordvenice2017.org/art-ideas/354

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/may/09/phyllida-barlow-review-venice-biennale-british-pavilion-sculpture