ROME – No one disputes that this is the most serious crisis facing both the U.S. and Europe since the end of World War II. Nor does anyone dispute that it is financial, and that irresponsible bankers all over the West are to be blamed. Looking deeper, we can also see that the Great Recession, as it’s being called, is an almost inevitable result of the de-industrialization of the West, whose beginnings were visible not yesterday, but half a century ago. Here are a few snapshots illustrating how the crisis is affecting Italians.

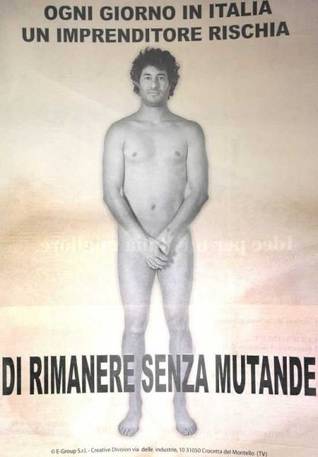

Item #1. Businessman Enrico Frare from Treviso, 36, is a manufacturer of E-Group winter sportswear. This week he purchased an entire page of the daily Corriere della Sera as a protest against the tough conditions of working in Italy. “Every day people tell me to delocalize but I want to stay in Italy,” he told reporters. Along with his photo, nude, appears the protest that, “Every day in Italy a businessman risks losing his underpants”. In English we’d say “losing his shirt,” but in any language the sense is that banks won’t lend money, no one invests in research or product development, consignments are slow, and in the end the younger businessman is abandoned on his own while the government doesn’t bother to help stop the overseas flight of the companies that made Italy’s fortune.

Item # 2. The head of the Partito Democratico (PD), Pier Luigi Bersani, age 60, was not exactly pleased when he learned from the newspapers that the mayor of Florence, Matteo Renzi, age 36, had called for the “dinosaurs” of the leftist parties in Italy to pack up and go home. The dinosaur insult came during a public debate in Florence Oct. 30, where the topic of primary elections for PD leaders was raised. For attacking the balding, cigar-chomping Bersani, along with Antonio Di Pietro and Nichi Vendola—three of the top leftist leaders—by name, Renzi was in turn assailed as all too new-media-savvy and, worst of all, too “Berlusconian.” The younger set, however, applauded Renzi, a front-running candidate for future national office, for such affirmations as, “This country has got to go back to being the nation of beauty, not of vulgarity.” He also complained that, whereas the best and the brightest of Italy go abroad to live and work, “no one, but no one, comes to Italy.”

Item #3. In a puzzling outburst, Labor Minister Maurizio Sacconi warned of the risk that terrorism may raise its ugly head, in the wake of jobs being lost. “Today I see a sequence from verbal violence to organized violence, which I hope will not lead into the homicidal events of only a decade ago, when poor Marco Biagi was killed in the context of a discussion very similar to what is going on today.” His words infuriated Susanna Camusso, leader of the leftist General Confederation of Italian Labor (CGIL), who retorted, “Either the Minister has proof of this or he should keep quiet.” At any rate Camusso also warned that a general strike may be called to protest government measures aimed at creating a more dynamic work force (translation: easier firing of workers). The kerfuffle was serious enough that La Repubblica had a bitter editorial cartoon by Ellekappa, in which one figure mentions that the Italian left is waking up. His buddy replies: “It’s a delicate moment. The risk is that if we have elections, we win.”

Item #3. The very least that can be said about the letter—and there is only one letter being discussed in Italy these days, the one signed simply “un abbraccio [a hug], Silvio”—is that it gained time for Italy to attempt to deal with its economic woes. It was addressed to the European Union leaders when they met in Brussels Oct. 27, and contained promises of the reforms that will get Italy back on track and a timetable. The stock market initially surged on the news that the EU top dogs had accepted the 15 pages of proposals—and then it emerged that the letter had been drafted in Brussels, then faxed to Berlusconi’s eminence grise Gianni Letta for editing and approval. So the substance of the letter was sent by the recipient to itself. (For a synthesis of the letter and its commitments, see: il

Sole 24ore [2])

Item #4. Several days before this, in a press conference (for the few who missed it), German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicolas Sarkozy had snickered publicly when Berlusconi’s name was mentioned in the context of prospects for Italy to deliver on economic reforms. Berlusconi himself brushed off the slight, saying that Merkel is friendly enough when they meet in person, but was showing off for her own difficult electorate at Italy’s expense. As for Sarkozy, he was trying to make points with his own electors, said the Italian premier. Nevertheless, the sneering tone of these two Euro powerhouses offended many here. But not all: Emma Marcegaglia, head of the Italian industrialists’ association Confindustria, said that, “We did not deserve to be treated like that, but at least it galvanized people [the government] into taking action.” By the way, Berlusconi said that when he’d later met with Merkel, she apologized—but then her press secretary issued a statement that this was untrue. She did not apologize for the snicker. But then Berlusconi has not apologized for saying she did.

Item #5 is yet to be written—how the spread moves, up or down (at this writing, +5.69). That is, the difference between the cost of purchasing 10-year treasury bonds in Italy and in Germany. In coming days all eyes will remain focussed on this.