UN. Reform: Discussed Yet Still Unrealized

In New York, as it has been for years, the General Assembly of the United Nations begins its first session. We met on the covered terrace in one of the many hotels that rise on the east side of Manhattan. Art Deco blends with modern New York City and the relaxed pace of Sunday brunch of mixes with the feeling of a vibrant city that is in perpetual motion. This is all in spite of the economic crisis that renews fears and uncertainty here and throughout the world.

Speaking with the Hon. Vincenzo Scotti, undersecretary of Italy’s Foreign Affairs, a man who has dedicated his life to politics, is like opening a book on the history of Italy and, in this case, its foreign policy. If you manage to corner him for a while, it is impossible to resist the urge to ask him about entire chapters of this book. And he responds in a clear, almost detached, non-partisan way.

Scotti's biography speaks for itself; it’s a mix of important political positions and intense academic work. He has been a leader of Italy’s Christian Democracy Party (DC), has directed several Italian governmental ministries, both interior and foreign, from labour to cultural and many others. Among government heads with whom he has worked, there are prominent names from the first republic: Andreotti, Cossiga, Forlani, Spadolini, Amato.

And from New York we cannot fail to mention that he founded, among other things, in collaboration with the late Judge Giovanni Falcone and then U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani, the DIA (Anti-Mafia Investigation Department), very important for the international fight against the mafia.

On the academic side, he has taught at LUISS (Libera Università Internazionale degli Studi Sociali Guido Carli), and was visiting professor at the University of Malta where he founded the Italian branch, over which he presides today in Rome. He is President of the Consiglio di Gestione della Fondazione Link Campus University.

We met him on a day of nearly autumnal colors while he is in New York for the UN General Assembly, but also to attend other special events including one that interests him in a particular way.

The symposium at Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò entitled “Two Mediterranean Statesmen at the Helm of the UN: Amintore Fanfani and Guido de Marco.” He begins to describe it in this way.

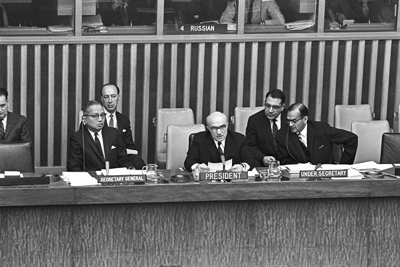

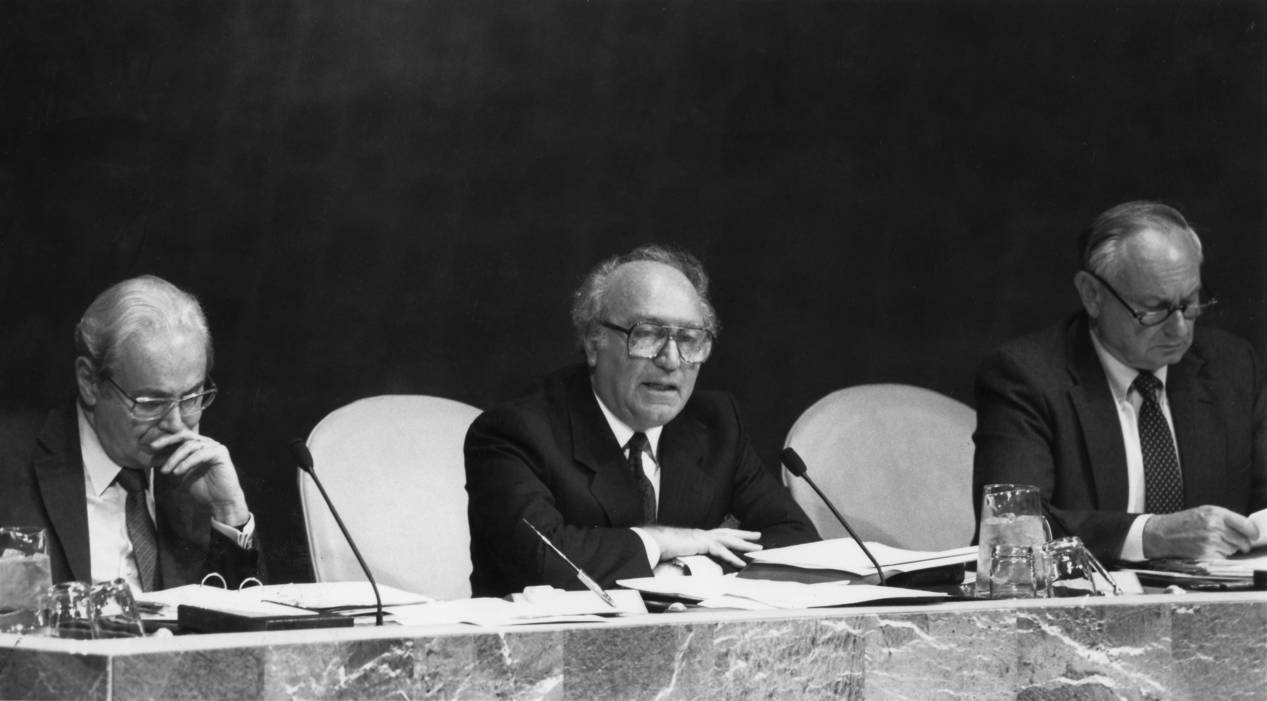

“It was 2008, the year of Amintore Fanfani’s centennial. At the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, during a seminar on him and Italian foreign policy, the idea came about to examine a particular aspect of his career, one that even researchers know little about – the time when he was president of the United Nations General Assembly (1965–66). So, with the support of the Foundation Fanfani, we decided to investigate this aspect and its relationship to the work of another leader, another Christian Democrat: Guido de Marco, former foreign minister and former president of Malta, who was in turn president of the General Assembly at a later period (1990–91). And it is important that both were from the Euro-Mediterranean area….”

There are many cultural and political affinities between the two. Both presided over the Assembly during periods when the trend was not to focus on the role of the UN: one at the heart, the other towards the end of the “bipolar era” when the conduct of the world was conditioned by two states that had been monitoring and managing interests, clashes, equilibrium. In Italian foreign policy, instead, there emerged the need to emphasize the role of the UN, to press the issue because the involvement of the United Nations had become central.

“We said asked,” the undersecretary continues, “why not organize a seminar to examine these issues and talk about the theme of the Mediterranean, which was crucial for both politicians?

From Amintore Fanfani to Guido de Marco – the president of Malta of Italian descent, perhaps less known to the general public, but no less important.

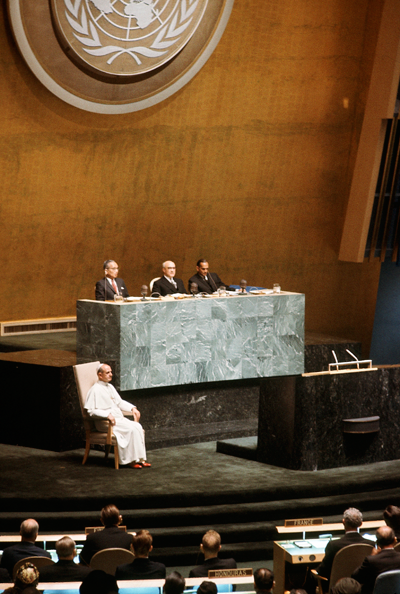

De Marco arrives twenty-five years after Fanfani’s presidency. And there is continuity between the two important statesmen. Both urged an evaluation on the process and the method of work at the United Nations, on the issue of transparency, responsibility, and democracy within it. He saw the need to revise this structure in 1946 when after World War II the victorious countries reserved the right to veto. This is now an anomaly for an organization that calls itself universal. For example, consider that today the African Union is not represented in the Security Council, despite that the fact that it is involved in more than 60 percent of the issues that the Council addresses…. We need broad inter-participation to give voice to all. It is no coincidence that with Fanfani for the first time a pope came to speak at the UN, giving a speech in line with the need to focus on the United Nations as a guarantee of peace.

The fact is that during Fanfani’s tenure our foreign policy envisioned, in a sense, a multipolar world, as it had been implemented by the end of the Cold War. In the vision of Fanfani – and de Marco – t e United Nations had to be not only an important forum for democratic debate, but central place for political decision-making.”

This symposium is taking place at a time when the discussion about UN reform is more alive than ever. It is no coincidence that it looks at these issues from Europe, even from the Euro-Mediterranean point of view…..

In the creation of the European Union, we find great insight into the future. After all, the EU anticipated one of today’s trends. The decision-making process at the United Nations cannot switch between two dominant players to 190 equal players. We need to find a different global architecture which is based on new experiences of government from the largest “regions” in the world. It is conceivable that traditional models are perennial, including the federal state or the nation-state. As with the European Union, something new is gradually taking shape which accelerates or decelerates depending on political will.

We ask him to discuss in the simplest possible way the cornerstones of UN reform which will hopefully take place….

First, we need to tackle the question of representation. The Security Council, which is the heart of the United Nations, and the General Assembly should reflect universality. It requires a presence that is reflected at its core.

Second, democracy is necessary – specifically, elections and not permanent seats, a system that allows the alternating presence of all nations in the Council.

Third, we need to find working methods that are more transparent and participatory. Here again is the issue of representation, not on behalf of a national state but a region, with rotating representation. The African Union has advanced this proposal to some extent. Europe, as well, must move in this direction. It is incomprehensible that during my tenure Europe has special status at the United Nations, and at the same time I ask for another permanent seat for Germany.

Fourth, the issue of accountability needs to be addressed – to monitor decisions and their implementation. Many decisions are not implemented and mechanisms are needed which will make them more effective. Consider the many crises in recent years, the Balkans, for example, to see the limits of the UN’s capacity.

The evaluation you suggest in the symposium on Fanfani and de Marco and looks at the fact that both presidents were from the Mediterranean region. And the Mediterranean is becoming more central to international politics.

The UN has a big challenge in the Mediterranean. There is what we call, with a bit of optimism, “Mediterranean Springtime.” We must avoid the possibility that each country will get into the race to increase their number of seats. Instead, it will involve a unified effort in terms of support, of help in state-building, in the creation of statehood. Not imposition from the outside, but support with full recognition of individuality.

And at the heart of these problems, the Palestinian question, of course, always remains. And here the role of the United Nations emerges again. It was important that this General Assembly – beyond the assessments that anyone can make – has undertaken, somewhat, the theme of peace talks. It is a huge responsibility to be entrusted with. For better or worse, the responsibility of the United Nations that cannot be side-stepped in the present situation.

And the Mediterranean today also means a tremendous amount of migration….

Certainly. And it is in this regard that we have put forward a set of proposals, ideas, and initiatives on the theme of interethnic and intercultural “new cities” as a symbol for the need to live in peace. There is no need to juxtapose one culture against another but there is a need to foster dialogue between them. And building cities according to a process of integration is essential. Cities today designed and managed more for separation and to prevent violence than for integration and to encourage dialogue. We are working to create a resolution that reaffirms, among other human rights, the right to full citizenship. And the full rights of citizenship can only be accessed by building a city of dialogue and peaceful coexistence.

During the conversation, many memories of Amintore Fanfani surfaced. We would like to conclude with this one, which we consider particularly appropriate and timely:

It was 1979. I was Labour Minister and Fanfani was President of the Senate. One morning we had planned a conference to discuss a measure by the Ministry of Labour. I had been in talks with unions throughout the night, I don’t recall about what, and I asked my undersecretary to arrive before me. I would have arrived as soon as possible, perhaps a few minutes late, once a deal had been reached. The discussion was at 10. I arrived at 10.15 but found that the session had been canceled by the president of the senate. Fanfani had already written a letter to the president of the council asking that I go and apologize to the senate for the delay. It was not conceivable to him that a minister would behave in this way toward a branch of parliament. The parliament was the center of the Italian institutional system and there was no commitment that could surpass it. And when he reopened the session, he told me: “This is a warning and a lesson. Institutions must be respected to the end. The government has an overriding duty to parliament.” It wasn’t about formality; there was a point in his message. Institutions will gain respect only if they are capable of conveying a strict and powerful image of themselves.

----

September 26, 2011 (02:45 PM ) @ Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò (NYU)

Symposium: TWO MEDITERRANEAN STATESMEN AT THE HELM OF THE UN: AMINTORE FANFANI AND GUIDO DE MARCO

In collaboration with the Italian and Maltese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

I Session – Welcoming Remarks

Cesare Maria RAGAGLINI – Ambassador, Permanent Representative of ITALY to the United Nations

Tonio BORG- Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs of MALTA

Saviour F. BORG - Ambassador, Permanent Representative of MALTA to the United Nations

Vincenzo SCOTTI – Minister of State for Foreign Affairs

II Session – Guido De Marco

Tonio BORG – Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of MALTA: “A Man for all Reasons”

Joseph CASSAR – Ambassador of MALTA to the People’s Republic of China: “Guido De Marco: Freedom first and foremost”

Salvino BUSUTTIL – Former Ambassador and President of the Fondation de Malte: “Guido De Marco: The International Environmentalist”

III Session – Amintore Fanfani

Franco CIAVATTINI – Centro Studi Fanfani - President

Camillo BREZZI – University of Siena: “Amintore Fanfani, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Italy and His Presidency of the XX United Nations General Assembly”

Umberto GENTILONI SILVERI – University of Teramo: “Fanfani's Term at the United Nations in the Eyes of the American Administration”

Piero ROGGI – University of Florence: “Amintore Fanfani at the United Nations: An Economist's Outlook on the World”

IV Session – Conclusions

Riccardo Nencini (Commissioner of the Region of Tuscany)

Lamberto Cardia (Fanfani Foundation of Rome)

Vincenzo Scotti - Conclusions

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.