Don Ciotti. For a Land "Libera" from the Mafia

From Gruppo Abele to Libera, from CNCA (Coordinamento Nazionale Comunità di Accoglienza - National Network of Welcoming Centers) to LILA (Lega italiana per la lotta contro l'Aids-Italian League for the Fight Against HIV) your movement has become a vehicle for civil and social mobilization. Why put so much at stake, both as a man and as a priest?

I want to clarify that the movement is not “mine,” but that it belongs to all those who have and continue to contribute their ideas, energy, and passion. Only “we” counts in social causes, not “I.” Secondly, these efforts began in northern Italy, in Turin where Gruppo Abele took its first steps in 1965. It spread on a national level as a result and that which “we” had always believed in came to fruition: “we” as in collaboration, the relationship between public and private, between institutions and citizens. It started in the early 1980s with CNCA (an association of communities committed to helping drug addicts), then with LILA when it came to time to address to the AIDS epidemic, and with Libera in the mid-1990s.

Why get involved? Because it’s the very same freedom that allows us to ask why. One cannot be free by oneself: one is free along with others in a collective effort and involves many people who are still denied freedom and dignity. Certain places and people in my life have obviously played a decisive role in this choice. I was lucky enough to have parents who loved each other very much and who loved me and my sisters very much, friends with whom I shared many life experiences, joys, and difficult times and with whom I learned to listen and appreciate the value of relationships. Of course faith has been fundamental in my life, a precious gift from meeting people like the cardinal of Turin, Michele Pellegrino.

When I was ordained a priest in 1972, Pellegrino, who simply called himself

“Father,” assigned “the road” to me as my parish with a warning: go on the road to learn, not to teach. The road, with its faces and its stories, its struggles and its vulnerabilities, its needs and hopes has remained my point of reference, a compass of faith that seeks to unite the heavens and the earth, to recognize the figure of Jesus in the many faces of human frailty.

If you could quote a biblical passage that explains the “why” of your work, what would it be?

I am a priest; my life is Christ, the gospel, the proclamation of his word. To seek God is to meet people. At the same time, my experiences allow me to say that you can seek man to find God. I speak of “seeking God” because you cannot obtain it automatically. God, for me, is the goal, the objective that puts me to the test everyday; it is research into the concrete articulation of life, in earthly choices.

I’m fearful of anyone who has understood everything and knows everything, who takes everything for granted. In this sense, the episode recounted in chapter 22 in the gospel according to Matthew remains crucial for me. Some people come to Jesus asking whether it is permissible to pay taxes to Caesar or not. They don’t go to meet with him, to talk to him; they want to pose a trick question. We know how the meeting goes. Jesus does not allow himself to be made fun of, he recognizes their wickedness, he makes them give him the money, and he asks the image and the inscription to go back to its rightful owner. But if the saying is clear, “Render onto Caesar that what is Caesar’s” what does “Render onto God what is God’s” mean? What is the image of God? Man is created – as we read in Genesis – in his image and likeness. And so it is our duty to give the money back to Caesar, but it is also our duty to give man, God’s creation, back to God.

Here’s the catch: we cannot return half-people or desperate people to God, or people who are used up, enslaved by poverty, loneliness, marginalization.... We must bring back whole persons who are free. This is the great challenge that I feel as a Christian: to bring about the right conditions so that all are free. And I’m not thinking solely of people who are rejected, exploited, crushed, those who are poor inside. In our society there are forms of immaterial poverty that are undermining the social body from the inside: indifference, resignation, the race for power, success, and money. The poor are also those who have lost a sense of life though they are able to live comfortably on this earth.

Can you talk about an incident that struck you as concrete proof of the practical effectiveness of your work that has encouraged so many... and the sort of obstacles you have encountered?

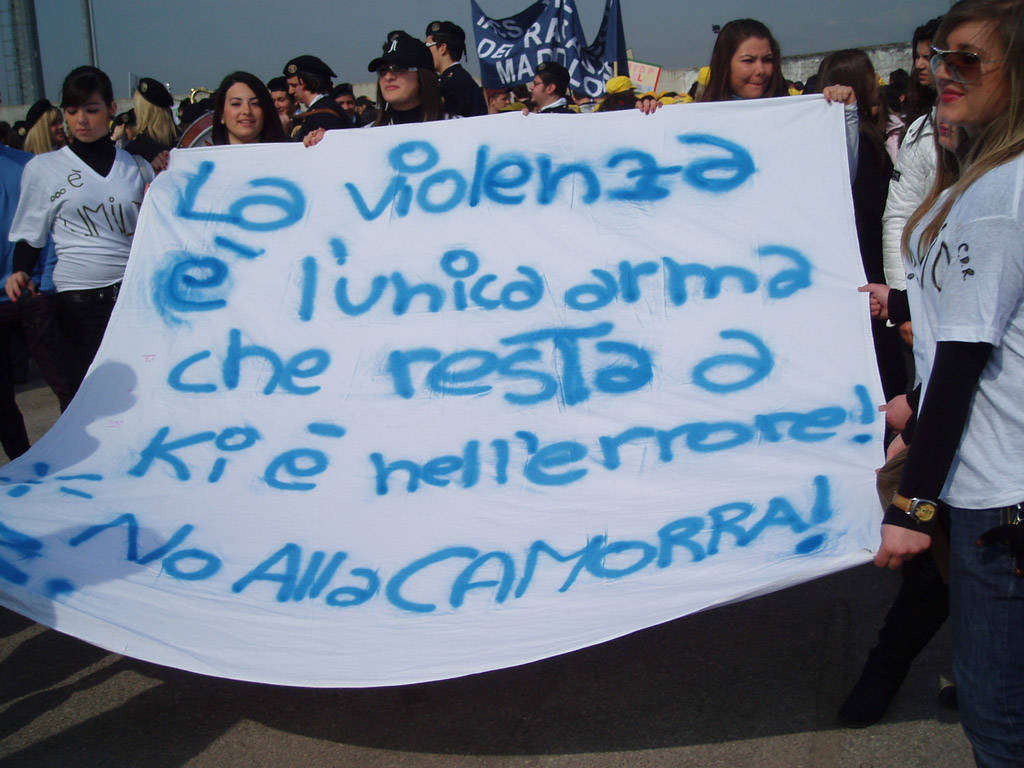

I don’t like to talk about “my” work. At the risk of repeating myself, I reiterate that only by working together can we ensure that people may live in freedome and with dignity. There are certainly many obstacles. Any change takes effort, and it also brings with it resistance, prejudice, and selfishness. Perhaps the most direct and explicit barriers, such as those posed by organized crime, is the corruption and intimidation they use to let us know that our commitment to confiscated assests is a nuisance. A great judge who coordinated the team for Falcone and Borsellino, Nino Caponnetto, once said that “the mafia fears the school of justice most of all; education cuts the grass from under the feet of the mafia culture.”

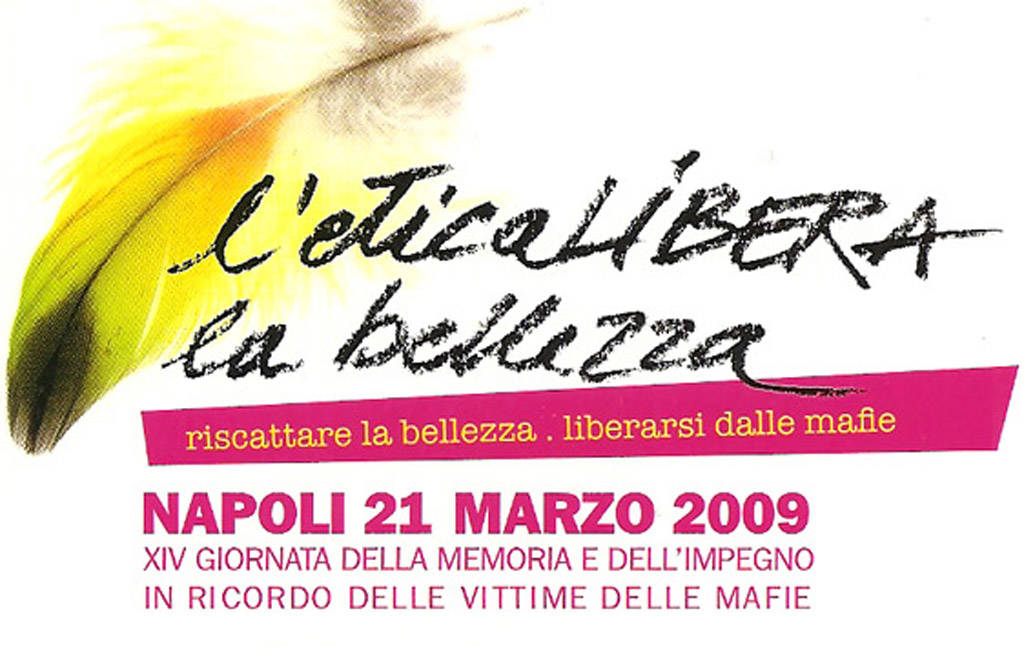

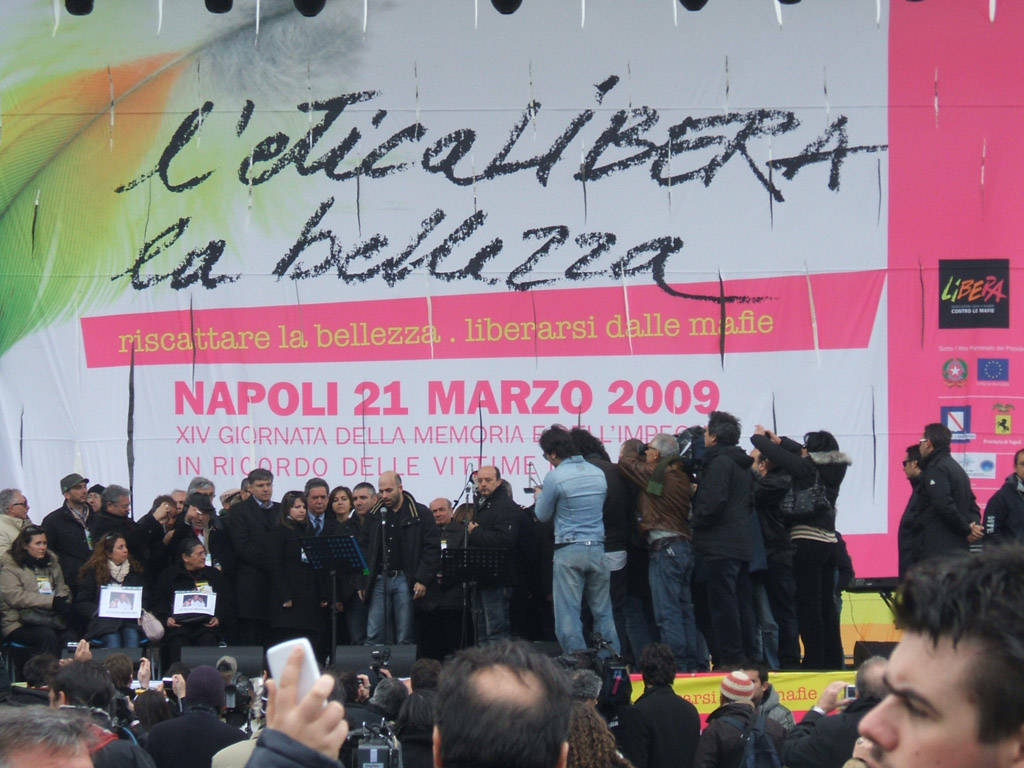

Libera is active in schools all over Italy, promoting education and training young people. Its mission is also to administer those assests that once belonged to mafia gangs, and it manages the cooperatives brought together under the consortium “Libera Terra.” It offers real jobs and life opportunities to many young people, and in this way it demonstrates that change is possible and eradicates the resignation and fatalism on which the mafia bases its power.

At the end of the film “I Cento Passi,” Peppino Impastato’s best friend says: “We Sicilians want the mafia because we are the mafia.” Thirty years after this young man’s death, do you believe that this phrase still reflects the mentality of the average Sicilian citizen?

In Sicily, as in other parts of the South, there are situations and opportunities that were unimaginable up until 15 to 20 years ago. There are many who like Peppino Impastato spread hope and found other people willing to get together and continue on his path. But it is a serious mistake to associate the mafia only with Sicily.

Certainly there are more marks of mafia oppression on our land than on others, but criminal organizations no longer operate on a local or national level but rather on an international level, one that is closely linked to the dynamics of economic and financial globalization and the expansion and deregulation of the markets. Libera was born out of our experience with FLARE (Freedom, Legality, and Rights in Europe), a network of associations that currently has a membership of more than thirty countries.

On May 9, 1993 in Siracusa John Paul II was the first pope to speak out against the mafia, calling it a “civilization of death.” Do you think this helped to awaken the public’s awareness of this issue?

The Pope’s condemnation remains a remarkable page in history that has certainly shaken the public’s conscience and marked a turning point within the Church, bringing to light some excessively cautious policies. It was a turning point foreshadowed by the document prepared for the Italian Bishops’ Conference in 1991 on Educating Lawfulness. “A Christian,” reads the document, “cannot be content to state the ideal and to affirm general principles. He must enter into history and deal with it in its complexity, promoting the gospel and human values of freedom and justice.”

Unfortunately, the mafia’s retaliation came quickly: the murderers of Father Puglisi first and then Don Giuseppe Diana, in Palermo and at Casa di Principe, soon followed John Paul II’s condemnation, one that arose from a breach of protocol. The Pope “surrendered” to the cry for justice after meeting the parents of Rosario Livatino, the judge killed by the Cosa Nostra in 1990 at only 38 years of age. Livatino was a believer who lived his faith in a radical way, combining the spiritual dimension with a commitment to social justice. These beautiful words were found in his notebook: “It would not have been asked if we had been faithful believers.”

You have written books dedicated to various social and civil issues, from drugs and prostitution to the mafia. You are still a journalist and columnist for several newspapers, including the monthly “Narcomafie” which you founded. Going beyond print media and facing the growing phenomenon of digital information, are you using the web and the tools it offers (such as social networks) to expand the promotion of your initiatives?

As with print media, even the ‘net is an excellent method that is recognized for its potential as well as its limitations. We should, however, look between the lines at the large numbers: quantity does not always mean quality, and as such, accessibility can be synonymous with superficiality.

The quality of content remains a key point. We must learn to use technology not be used by it. For this reason, technological progress must be focused on the cultural and ethical growth of mankind, to help us to become a stronger community in terms of proximity and justice, to compel us to better understand situations so that we can improve them. If such awareness is lacking, there is the risk that navigation in the virtual world becomes an escape and an opportunity has been lost.

I still firmly believe in this new frontier, and as with Gruppo Abele and Libera we feel the importance of having a presence there with a three-fold mission. The first: to help a user who is familiar with technology to ward off the illusion that telecommunication can replace face-to-face contact. The second: to promote and practice a culture that involves the discipline of research and depth. The third: to broaden interest in and passion for causes that are currently ignored, obscured, or understood superficially through trivializing stereotypes.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.