Looking at Life Through the Eyes of Lisetta Carmi

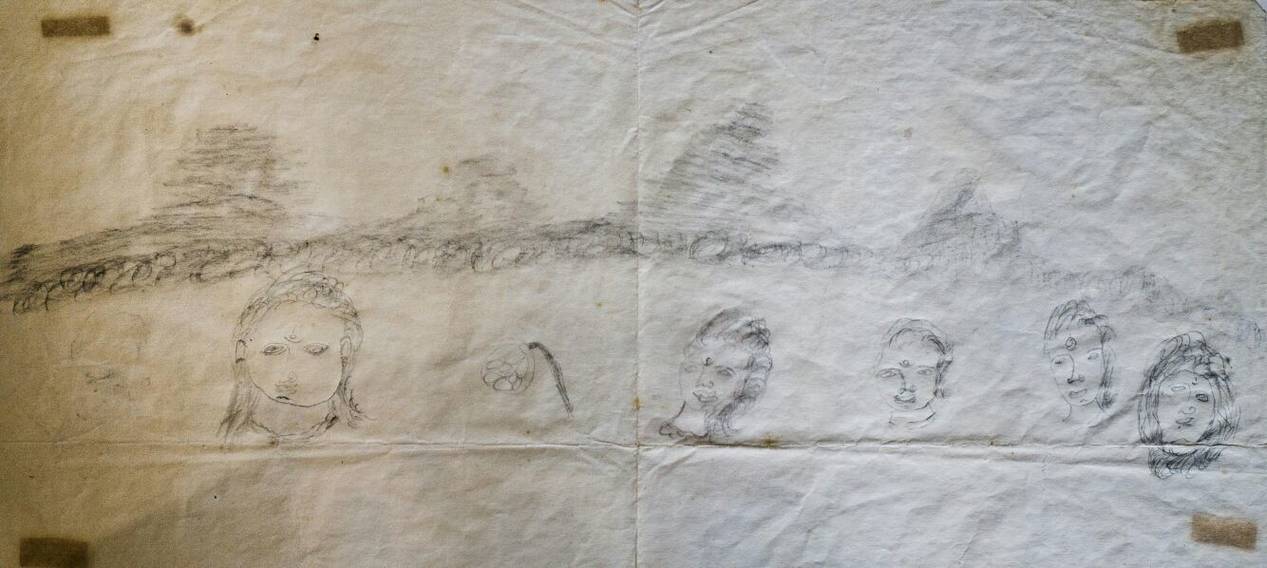

When she looks back at her life, Lisetta Carmi maintains that, at 92, she has already lived five. The drawing of her made by her spiritual guide, Babaji Herakhan Baba, was right. Each one of the five faces portrayed among lotus flowers, represents a different life, ranging from that of the musician, the photographer, the community leader, the reborn musician and the silent bystander.

Today, Lisetta sits down on the chair in her studio and looks out the window at Cisternino, the adoptive Apulian town that has welcomed her decades ago but that has also judged her and deemed her a bit “different.” Surrounded by her photographs and books, she looks at you with piercing, green eyes, that are frosty yet welcoming at the same time. Eyes that look beyond the obvious and go in deep, when they stare both at life itself and life captured by photography.

Above all, Lisetta Carmi is known as a photographer whose work has been compared to Henri Cartier Bresson's. Once you discover Lisetta's unique body of work, the images of La Gitana, La Novia and La Morena, the transvestites of Via del Campo in Genova back in the 1960s-70s, but also those of her native city's dock workers, of a newborn coming out of his mother's womb or of American poet Ezra Pound are imprinted on you for life.

“I have often asked myself 'where do I come from?'” Lisetta asks us directly, “How was I able to look at the world and all those human beings in such a natural way? When I started taking pictures I didn't have any practical training. How did my very first photos, taken here in Puglia in 1960, during a trip to the Jewish catacombs of Venosa with musicologist Leo Levi, have such strong meaning and shape? I come from a special family, a family of amateur photographers who have silently infused in me the desire to understand the world through my images, images that capture life. When I looked at the photos taken by mom and dad I used to tell myself that I would never be able to be as good. Now, several lives later, I can say that I was a photographer for only 19 years but it might as well have been 50. I was always on my own, camera in hand. My passion for my fellow human beings has brought me to witness extreme situations in a world that is unjust yet fascinating at the same time. A world that I didn't always understand, so I photographed to understand life. ”

As a child, Lisetta was a young pianist whose family was persecuted by the Fascist regime. In 1938, she was kicked out of her school in Genova at 14 because of their religion and had to cross the border into Switzerland on foot. “With one hand I was helping my mother, Maria Carmen Pugliese, and with the other I was carrying sheets of music.” Bach, to be exact. Her passion turned her into a promising concertist but she didn't really enjoy performing in front of strangers. One specific event led Lisetta, a young woman who was focused on marginalization and social injustice because she had experienced them on her own skin, to her second life.

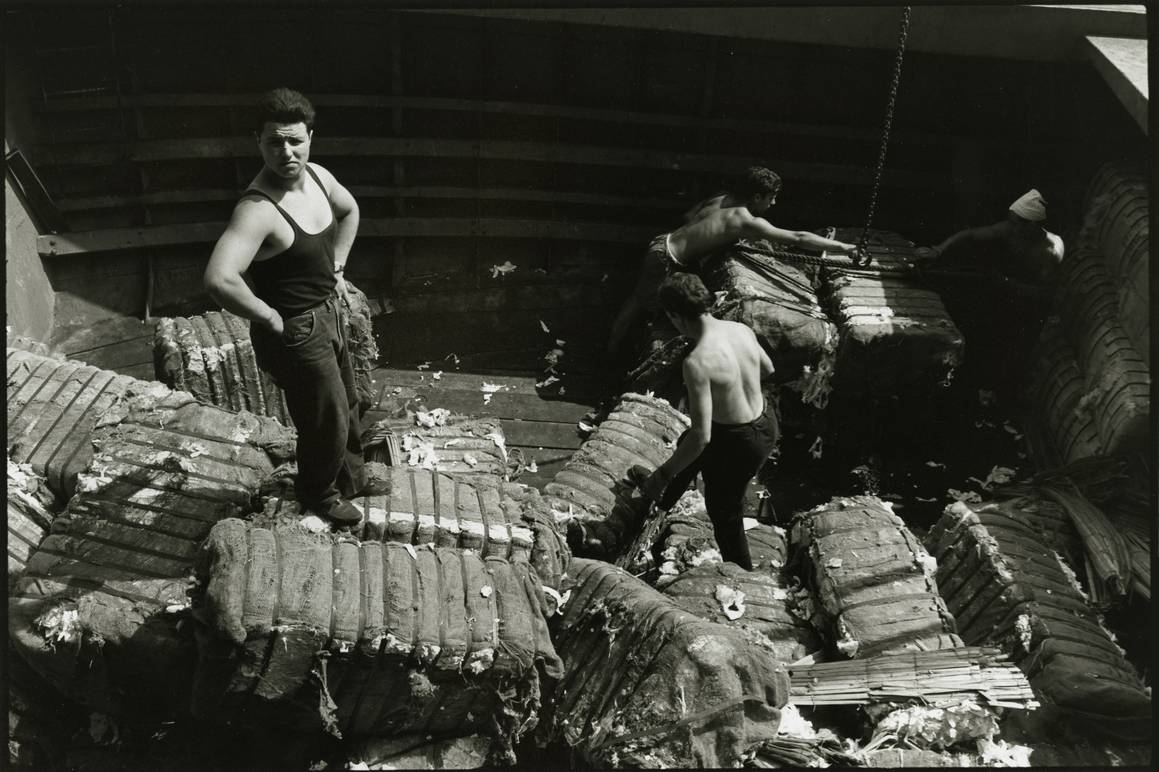

“Back in Genova, I wanted to participate to a march in support of the labor rights of Genoese dock workers, but my music teacher forbade me to. He said it was too dangerous, he said there was a risk that I'd break my hands. I didn't care about that.” That's when her life as a photographer of the outcasts, the less fortunate and the persecuted gained the upper hand. “I used to tell my dad that I was disappointed I had not been taken to the concentration camps. I knew I could have helped others, and that desire to help never abandoned me.” Her father was the one who gave her her first camera and Lisetta used photography to give voice to those that were rejected by society, who lived in horrible situations and were crushed by the powers that be.

Lisetta pretended to be the cousin of one of the Genoese dock workers and started capturing the men's working conditions and difficulties on film. That reportage, commissioned by Cgil, the Italian General Confederation of Labor, is a powerful document of the strong social and cultural identity of Genova in those years, but it also was the first step down a path of vilification that brought on the photographer's social commitment.

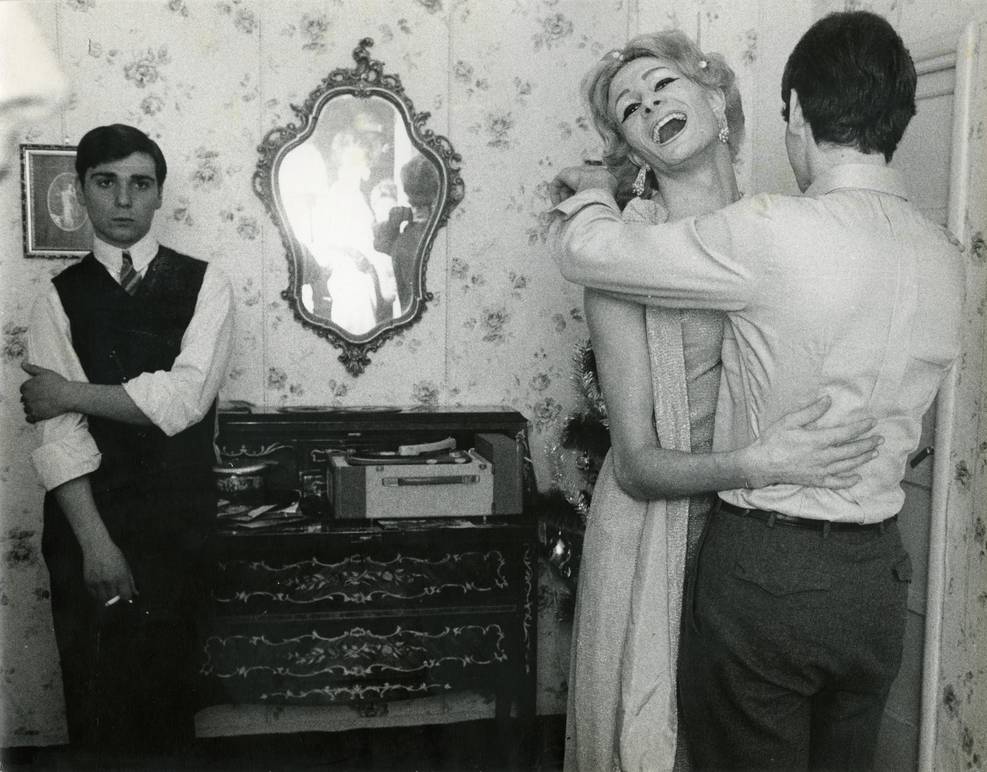

One day, in 1965, a friend invited Lisetta to celebrate New Year's Eve in Genova's Jewish ghetto, in Via del Campo, where a group of homosexuals and transvestites had settled. Slowly she befriended the members of the community as she started shooting their portraits, which she'd give them as gifts. “In those years together, from 1965 to 1971, I have protected and admired them, I've lived through their suffering, the violence and the degradation of their lives. I just wanted to get to know them, and I did.” A collection of all her work was published in 1972 by the title I Travestiti, thanks to Sergio Donnabella as Lisetta had no intention of doing anything with her work. “I had not photographed them for commercial reasons. The publication faced some obstacles as booksellers refused to showcase the book. It was considered scandalous and even Cesare Musatti, a renown psychoanalyst, refused to present it because he considered transvestites people who belonged in the hospital.” However, there were also those who did support the book, and that includes Dacia Maraini and Alberto Moravia.

The experience with the homosexual community didn't have only a professional impact on Lisetta, but also a deeply personal one. “Thanks to them, I learned to accept myself. When I was a child, I looked at my brothers, Eugenio and Marcello, and I wanted to be a boy. I knew I didn't want to get married and rejected the role society assigned to women. The transvestites made me ponder over the right that we all have to determine our own identity. It took me a while, but I got to embrace the joy of being a woman.”

Among Lisetta Carmi's most appreciated work, we also find her portraits of American poet Ezra Pound, taken during a brief encounter, 4 minutes total, in his house in Rapallo. Shot on February 11, 1966, they are just a few in number, 12 final shots out of 20, yet they are unique black and white testimonies that capture “the solitude, the desperation, the belligerence, a gaze at the infinite, everything that cannot be said with words and the dramatic greatness of the poet.”

Lisetta was invited to join Gaetano Fusari, the Director of the ANSA Press Agency of the Genova branch, who was supposed to interview Pound. She went with her Leica 35 mm. They knocked on the small house's door, and after a few moments of silence, Pound walked out, as if lost. He just stood there, in his robe and slippers, and didn't utter a single word, despite our presence. Lisetta just started shooting and shot and shot until the poet's retreat into his house.

Pound was old and sick, having survived thirteen years of imprisonment in the psychiatric ward of St. Elisabeths Hospital in Washington. “When I developed and printed the twelve shots I had selected, I saw in them exactly what I felt as I was taking them. We did not meet the poet, we met the shadow of the poet.” Wanting to share her experience with Pound's family, Lisetta sent them the shots which later became some the most known images of the poet, used in numerous books dedicated to his work. That small reportage is still considered one of the most significant moments in Italian photography. Those images also earned her the Italian equivalent of the Niepce Prize and praise from the great Umberto Eco, who said that “Lisetta's images of Pound tell more than it has ever been written about him, his complexity and extraordinary nature.” “I captured more than his physiognomy, I captured his pain of living.” Pound died years later, in 1972, and before his house was sold, Lisetta asked his family permission to go back and shoot “the small house by the olive trees in color.”

Lisetta continued working as a photographer while traveling the world - Afghanistan, Latin America, Israel, Palestine, but also Sicily and Sardinia are some of the places that she and her camera visited – while living both in Genova and in Cisternino, where she had purchased a place years before.

In 1976, everything changed and the transition from one life to another happened after a trip to India where she met a sadhu (holy man), Babaji Herakhan Baba, who became her spiritual guide. “He called me to him and he showed me life's deepest truths. When I saw him for the first time, I felt I was living through the times of Jesus, where the disciples were waiting for their teacher. I went to introduce myself and said 'Babaji, I'm Lisetta,' 'Your name is Janki Rani' he replied, and I sat next to him. I was in ecstasy, I looked at him and I could see that he was the manifestation of God in human form, that he was pure love.” That first time Lisetta, or rather Janki, spent 25 days with the divine teacher. During those days she witnessed the announcement of Babaji's Mahakranti prophecy that said “that the world as we know is about to end. 75% of humankind is about to be destroyed and great part of the world will be covered in water. Yet the remaining humans will be able to face the water and the fire and start anew. The disciples were scared but I was not. I heard the prophecy but all I could hear was the word “freedom.” That is how God is giving us a chance to wipe out all the negative and start over, with the triumph of love, brotherhood and harmony.”

After 25 days Lisetta had to return to Italy to take care of her elderly mother, but through the years she went back to India several times. During one of these times Babaji told her to build an ashram in Cisternino, “a place where people could come with their problems, doubts and ailments looking for spiritual solace and guidance. I asked Babaji what he truly wanted from the ashram and he replied that it had to be a place of transformation for people where they could purify their body and soul.”

Photography thus became a distant memory and, although completely inexperienced, Lisetta ventured on a new mission without giving it a second thought. The Bhole Baba center was opened in 1986 and it's identical to Babaji's ashram in Herakhan, India. “Life at the ashram was and is the same for everybody, as we are all the same. Nobody comes first and nobody comes last. We are all equal.”

In 1992, while she was president of the center, Lisetta created la Voce di Cisternino, a bi-annual publication featuring essays, news and announcements of events taking place at the ashram. She penned Notizie da Cisternino, an editorial signed as Janki Rani. In 1998, thirteen issues later, in her editorial, Lisetta announced that it was time for her to leave the ashram but she was still available to speak to whoever wished to do so. “It was time to work on myself. I often wondered how I had been able to live in such a challenging communal environment for so long and I was looking for solitude.”

Personal connections brought Lisetta to collaborate with a former student of hers, Paolo Ferrari. A physician and scientist, but also a psychotherapist and musician, Ferrari is the creator of a method called “Asistema in-assenza.” Lisetta had not played the piano in about 35 years but she was invited to attend Ferrari's seminars in Milan where she'd play at the end of each session. “The concept is rather difficult to grasp, but the margins of absence open up vast and unexpected horizons of freedom. Getting to know Paolo's ideas and getting close to music again was a real miracle. Up to that point I had learned from life everything I had to know and I was then living a reversal of roles. The teacher became the student.” After six years of weekly trips to Milan, where the seminars were taking place, Lisetta understood that the experience had come to an end. “Life was starting to repeat itself and it was time for detachment and silence.” Is it the same silence of Ezra Pound's desperation or of the nameless dock workers of Genova?

Lisetta is now living a new stage of her existence, the one she considers her favorite. Her life is exactly how she wants it to be, made of silence and solitude. “I sit on my chair” - the same chair mentioned at the beginning of this article - “I close my eyes and I just sit here. I don't eat much, I drink only lukewarm water and I take care of the house. I don't listen to music. And when I am asked who has taught me how to take pictures, I reply, life. Because I just looked at life.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.