As a college teacher, my mother taught at a city university which, after a large shakeup that included a merger and the institution of the revolutionary multicultural policy of open enrollment, became New York City Technical College. Looking back on her career now, it was very much shaped by the changing fortunes of the humanities majors from the sixties through the eighties.

In the eyars immediately following the launch of Sputnik, things had been different. Thanks to the Cold War, and fears that the Russians were getting an edge on the United States in terms of technology and the overall strength of the intelligentsia, the American government subsidized higher education to an amazing degree, and the humanities majors benefited from the initiative as well as the sciences. My mother’s scholarship was probably a result of such monies. Unfortunately, by the time she finished graduate school, and began looking for a teaching career, the bottom fell out of English departments in higher education, especially in the City University and community colleges system. Open enrollment meant that colleges were made available to everyone, including those who had been cursed with dreadful grade school education, those who were new immigrants, and those who had gotten their GEDs. The democratization of college, and the end to elitism, were noble goals, but those, effectively, led to the watering-down of the literature curriculum at her college, and many others. The degree of remediation required to try to teach these legions of new students basic writing skills to enable them to survive life in even a two-year-college, let alone a four-year one, was considerable. There was little way colleges could expect students with little to no ability to read or write in English to be able to understand the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne or Herman Melville, so my mother only managed to teach “Bartleby the Scrivener” and “Young Goodman Brown” for the first couple of years of her career before she wound up teaching basic grammar and the four-paragraph essay to remedial writing students for the bulk of her career at New York City Technical College. I haven't talked to her much about it, but from where I was sitting, she appeared to like teaching the material, but found the grading tiresome in the extreme. In fact, despite her short number of hours in the classroom, minimal committee work, and no scholarship expectations, she worked like a mule grading and regarding a dozen essay assignments granted to upwards of two-hundred students a semester. The commute from our family home in Staten Island to what she dubbed “glorious downtown Brooklyn” via the eternally traffic-jammed Brooklyn-Queens Expressway left her drained much of the time, and often horrified at the prospect of actually having to cook dinner and do housework every night after returning from work.

(One would think that dad would have held up his end here, but he didn't, really. He had too much fun hanging out with me when mom was at work. Playing Stratego. Going to the park to look for Preying Mantises. Watching his favorite old Hammer horror movies on our brand new, cutting-edge-technology VCR. It was fun. But not for mom.)

Some of my most vivid memories of mom from childhood involved her sitting on the couch, surrounded by piles and piles of little blue examination books, grading essays with a red pen while the daytime soap operas All My Children and One Life to Live played on mute with the closed-captions on as a minor distraction from the drudgery of the grading task. She would have enjoyed the job more had the essays been better, and had she not had the same students upwards of three semesters in a row after failing them repeatedly. Technically, students were supposed to be expelled after failing remedial writing twice, but it never happened, so she sometimes complained of having the same student four or five times. Eventually, she would pass such a student on, but she had deep reservations that such a student belonged in college when they would turn in a four-page paper on the death penalty that looked like this:

Professor CD Icepick

The Death Penalty

i don’t like death penalty.

I was absen allot this class, cuza my nu girlfriend. I met her at a bar called gogos. She had a tattoo over her az. it said daddys trash. i said whose ur dady. She said you are. and u can iamagine, professor, the great sex we had after that. in the bar bareassemt. i put her pantez in my mouth and my cok inside her az right under her tattoo. i cummd. It wuz cool. and we fuk allot. Evr sinz. On cars and in barassments and in alleys and in all sorts posishuns.

That is why i am absen allot.

I need an a in the coarse. Please give it to me so i can take over my father’s gas station while he is in jail.

Thank you.

Icepick

It was demoralizing for my mother, being forced to grade hundreds of papers of this quality throughout the semester, and a lot of them tended to blur into one another. However, looking back, this essay from Icepick did make an impression on her. She never forgot it. When Icepick complained about the F she gave him, he said, “How did I fail, man? I know how to write!” Icepick had lots of gold teeth and my mother was frightened of him.

“The essay was on the death penalty and you didn’t write about that topic.”

“But I wrote a good story about me and my girlfriend. You fail me you tell me I can’t write, I feel bad about myself, you know? That’s not good to not make me feel smart, you know? Instead, I feel like crap, you know? Like I can’t write, you know?”

“It doesn’t matter if you did a good job on another topic,” my mom explained. “I gave you one and you didn’t follow directions. If you go to the hospital to have your gall bladder out and the surgeon does a really great job removing your lung, he shouldn’t get credit for that.”

“But come on, is what I’m sayin’. Is all, you know?”

“Icepick, even if the assignment had been ‘Sex is fun,’ it still isn’t a well-written, long enough, or grammatically correct essay.”

“But come on, is what I’m sayin’.”

“No, Icepick.”

“Is all I’m sayin’, you know? Come on.”

“No.”

“Aw, man! Whatdafuk, man?”

“No, Icepick.”

“Man!”

Mom never showed me her students’ work, but she would sometimes give me a handful of blank examination books to doodle in and write in. For the most part, I didn’t write cohesive stories, or even do more than draw funny shapes and color them in. Still, I remember one time when I took a stab at storytelling. I wrote an adventure story called “The Streets are Cracking.” I used an impressive array of Crayola crayons to draw a scene of a little stick man walking along my idea of a city block, which boasted a cartoon tree, two houses, and a straight line across the page representing the street. On the next page, I drew a big crack appearing in the street and gave my stick man a shocked expression. I flipped another page, and picked the most bizarre color I could find from the box of 68 crayons – Periwinkle. So, on the next page, I drew a big Periwinkle demon hand reaching up from the crack in the street. The second-to-last page saw the hand drag our hero back into the hole in the ground. I couldn’t figure out where the story should go from there, so I thought that was a good place to end it.

I showed the story proudly to my mother.

“Very good, Marc. I have a student named Icepick who wants an A for a terrible paper. If I give him an A for what he wrote, what does that mean I should give ‘The Streets Are Cracking?’ A++++?”

I had no answer for her, but it sounded like she was praising my work, so I smiled.

On another day, I decided I would use one of the blue books to write a letter to my favorite dinosaur, the brontosaurus. As it turned out, my letter was pretty short, and only used up half of the first page of the blue book, because I realized that I couldn’t think of all that much to say that a brontosaurus would be interested in reading. So I decided to make it about him, instead of telling him about me. This is what I wrote:

“Dear brontosaurus,

Watch out for the Tyrannosaurus Rex. He has sharp teeth and is a meet eater. You are a plant eater and have no teeth. Be careful.

Sinserly,

Marc”

I found an envelope large enough to put the blue book in and wrote on it my name and address in the return address section. In the recipient space I wrote,

“Mr. Brontosaurus.

The desert.

The past. B.C.”

Then I put my zip code after B.C. because it was the only zip code I knew.

By the time mom was done teaching, doing the housework, and grading papers, she was often too exhausted to do anything more than watch television. Her eternal favorites were Jeopardy!, Mystery!, and Masterpiece Theater, but she spent the eighties checking in on shows like Dallas, Quincy, The Cosby Show, Family Ties, Matlock, Golden Girls, Empty Nest, Amen, and 227, as well as miniseries like North and South, The Thorn Birds, and Jesus of Nazareth. I enjoyed watching all of these shows with her, sitting Indian style on the carpet in front of the television set, as she lay spread out on the couch next to me. I would always make it to the end of each show, but she had a tendency to doze off with ten minutes left to go of everything she watched, so she spent years watching mystery shows like Matlock and never finding out who the killer was. In some ways, she preferred Columbo because each episode began with dramatizing the killing and the only mystery was how Lt. Columbo would gather enough evidence to arrest the killer. If mom missed the moment the killer was arrested, that wasn’t so bad, because at least she knew who the killer was.

Even though she did watch a lot of TV, she also found a lot of time to read, and I always liked watching her reading, even when I was too young to read myself. Mom’s favorite author was Agatha Christie, and she had the entire mystery collection. She read the books voraciously, going through them at an amazing clip – sometimes one or two books in just one sitting – and there were roughly eighty books, which meant that, by the time she finished the eightieth book, she had forgotten the first one, and went through them again. Of all of the Christie detectives, mom’s favorite was Miss Marple, the little old lady who used gossip and a social network comprised of cooks, nannies, and dowagers to solve crimes. Mom liked Hercule Poirot a lot less, since she found the little Belgium effete, fussy, and annoying, but she really hated Tommy and Tuppence and had not a kind word to say about them.

“Well who are Tommy and Tuppence?” I asked one time.

“What?” mom asked. She was tone deaf and a little hard of hearing.

“Who are Tommy and Tuppence?”

“They’re terrible!” she cried.

“How?”

“They are so terrible I can’t describe them.”

“Are they two little boys? They sound like Tom and Huck.”

“No, they’re a married couple.”

“Who solve crimes?”

“Yes and no. They may be spies.”

“Spies? Really?”

“Well, not really. They’re just terrible.”

I shrugged. “Well, they’re not famous. I would have never heard of them if it wasn’t for you. I’ve seen Poirot movies on HBO, so he’s famous. So I guess the world agrees with you. No movies for Tommy and Tuppence.”

“They don’t deserve their own movies!” mom said emphatically.

And that was the last time we ever discussed Tommy and Tuppence.

At a certain point, mom started to miss the hardcore literature she had read as a graduate student and began to feel guilty about the reading list for her comprehensives that she never completed. While she had no intention of finishing her doctorate, or writing a dissertation, she decided it was time to hit the classics again, and drew up a nice, long reading list. In one summer, she read seventy-five books. This feat literally amazed my Uncle Al, and he has not stopped referencing it since he first heard of it. During a recent gathering of the extended family my uncle, who looks a bit like both Jackie Gleeson and Paul Sorvino, started praising my mother to her cousin Linda, and her husband, Ron Telli.

“You know who the smartest person I ever met is?” Uncle Al asked. “My sister. She is so smart. She read eighty books in a summer. It was ten or twenty years back now, but I still can’t get over it. I couldn’t read eighty books in a lifetime. I’ve read one book. Rush Limbaugh’s The Way Things Ought to Be. Great book. But that was all I needed. My dad read two books in his life: the Bible and The Godfather. But my sister! To have that patience! That love of reading! I get bored too fast. I can’t even read to the end of the list of eighty books she made. I read the first ten books, didn’t recognize any of the titles, and I stopped reading the list. Compare that with my sister!”

Ron, who is the spitting image of Ben Gazarra, nodded appreciatively, but didn’t seem to be making enough of a fuss over my mom to please my uncle. So my uncle took his praise up a notch, at Ron’s expense. “I bet you haven’t read eighty books, Ron. You’re not a reader.”

“Speak for yourself! I read.”

“You read? Sure, you read.”

“Linda and I read ourselves to sleep every night.”

“We do,” Linda confirmed.

“In fact,” Ron elaborated, “she always reads the ends of her books first, to see if she likes how they end, and then decides if she’s going to make the commitment to read the whole book. She almost always chooses to read it, but sometimes she switches to another book and checks that ending. She does this until she finds an ending she likes. It annoys the heck out of me, so I’ve started stapling the last chapters of every book in the house closed so she can’t read them.” He mimed the act of stapling with his hands as he said this.

“Which winds up being a problem even when I do cave in and read it your way, because when I get to the end, I tear the pages to shreds trying to get the staples out and then I don’t know how the books end,” Linda added, miming pulling the staples loose and tearing the pages apart from one another.

Uncle Al looked unconvinced. “Okay. You read yourselves to sleep every night. I still bet you aren’t as smart as my sister.”

“This isn’t a contest, Al,” Ron said in a low voice.

For most of my early years, the only books I dared to read were the ones I was assigned in school. Sometime around third grade we started getting assigned books like The Secret of NIMH, Little House on the Prairie, and Ramona the Brave, and we were asked to choose books to read on our own. Most of the boys opted for The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and the girls picked A Wrinkle in Time. The books I was most eager to read were Jane Eyre, Great Expectations, Dracula, and Frankenstein, because those were the books I’d seen wicked awesome black-and-white movie versions of thanks to PBS, but each time I tried to read one of them as a book, I found the language was too difficult. In fifth grade I read about forty pages of Frankenstein before realizing that I hadn’t understood a word and gave up. My attempt to read the Book of Genesis in the Bible around the seventh grade also went badly because I thought the writing was too simple. I also didn’t think it was as entertaining as the creation segment from Fantasia, and was annoyed that the creation story didn't mention any dinosaurs at all, let alone the brontosaurus, so I gave up on it around the time God put enmity between the daughters of Eve and the serpent’s descendants.

Whatever problems I had with serious literature as a fifth-grader, I still read a bit. Whenever I did have to read a book, I sat in the overstuffed armchair next to the plush couch mom laid down in and we read together for several hours. She was always a faster reader than me, so the one time I beat her to the end of a book was a big accomplishment. I’m not sure exactly how old I was when I started regularly reading next to her, but my best guess puts me at around the time I was eleven or twelve. Around that time my books of choice were entries in the Wizard of Oz series, which I got into because I loved the film Return to Oz (and despite the fact that I hated the film The Wizard of Oz because Dorothy was too old and I thought the songs were cheesy). There were fourteen books in the Oz series and I had bought the whole series with my allowance money, because I wanted to have the whole collection of L. Frank Baum books the same way that mom had all the Agatha Christie books. (There were several supplemental Oz books by Ruth Plumbly Thompson, but they were $6 instead of $3 and not in my price range, so I didn’t buy any of them. Well, they were, but I got $5 allowance a week and getting a book by Thompson meant saving up for a week, when I could buy a $3 book instantly. I used my allowance for instant gratification and never saved for anything.)

Unfortunately, my collecting mania was stronger than my desire to read and I only actually ever read five of the Oz books, The Wizard of Oz (which, again, is far better than the film), The Road to Oz, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, Tick Tock of Oz, and The Emerald City of Oz. The Road to Oz was cool because it featured a sailboat that cut through desert land, but my favorite single moment occurred at the epilogue of The Emerald City of Oz. It ended with a bankrupt and evicted Auntie Em and Uncle Henry leaving Kansas behind forever and moving permanently to Oz with Dorothy. Once they get over the initial shock that Oz is a real place and not a figment of Dorothy’s imagination, and they settle in, they point out a truth that Dorothy herself never picked up on: every animal in Oz can speak except Dorothy’s dog Toto. Wondering if Toto can talk, but chooses not to, Dorothy kneels beside her dog and says something like, “If you can talk, you must not like it. But please just let me know if you can or not and you never have to speak again. Can you talk?” At this point, Toto reluctantly barks, “Yes,” and scurries away.

I give that moment the award for the cutest moment in the history of literature.

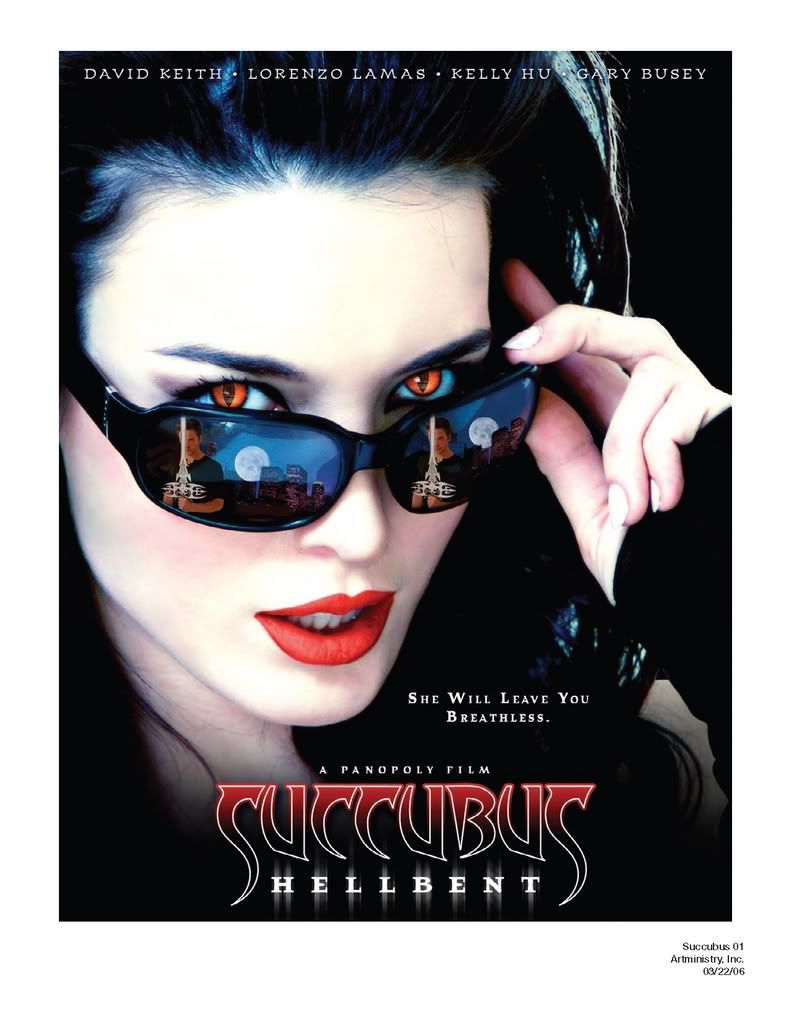

In addition to the Oz books, I also actively read a lot of television tie-in books, especially those related to my favorite shows: V, Star Trek, and Doctor Who. I remember the V book Prisoners and Pawns by Howard Weinstein, which featured my favorite subordinate villain from V: The Series, Lydia, in the spotlight. I also remember that Lydia got to have herself some sex in the book, and it was the first time I’d ever stumbled across a sex scene in a book. (There was no sex in the Oz series that I remember.) As tame as it was, since most of it was implied or happened “off page,” I remember getting a lot out of that sex scene in Prisoners and Pawns. I also remember being terrified by a Star Trek novel called Demons, by J.M. Dillard, which involved Captain Kirk and the gang getting taken over by monsters. I also took to collecting a series of books that novelized Doctor Who episodes, most of which were little more than shooting scripts with some description of setting and facial expressions strategically inserted by "author" Terrence Dicks. The reading level on those books was actually too simple for me, but I liked Doctor Who too much to care. And, in some cases, the novelisations were of "lost episodes," so it was my only access to certain stories that the BBC failed to archive. Otherwise, the only Who novels that awakened my interest were those written by Ian Marter, an actor from the series who was a better writer than Dicks. Marter was also was one of the first to write an original Doctor Who adventure that was not based on a televised episode, the fun spy romp Harry Sullivan’s War.

I also enjoyed the Dungeons and Dragons books that were part of the Endless Quest series, most of which were by someone called Rose Estes. Designed to be multiple potential narratives in one book that gave control of the plot to the reader, the Endless Quests offered readers the opportunity to choose which story they wanted to read by giving directions to the hero. The early Endless Quest books were primitive and limited and featured silly moments like this:

– page 13 –

“You come to a fork in the road. On the left path you see dragon tracks. On the right path you don’t.

If you want to go left, turn to page 22.

If you want to go right, turn to page 23.”

I decide to follow the dragon tracks and turn to page 22. This is essentially what it says.

“You see a dragon and you don’t have a shield. He roasts you alive. The End.”

So I went back to page 13, checked the other option, and then flipped to page 23 to continue the story on the winning path.

Books that came later, many of which were also written by Rose Estes, got more sophisticated and were better at offering multiple fruitful storylines rather than an illusion of choice created by a series of choices that lead to death and essentially one right way of reading the book to get to the end.

Doctor Who eventually had its own version of the Endless Quest book, The Rebel’s Gamble, which was over 1,000 pages and gave me weeks and weeks of reading fun. It was about a member of General Lee’s army who, thanks to an accident in the space/time continuum, gets a hold of a history of the Civil War from the future and uses it to warn General Lee of his defeats in advance, thereby changing the course of the conflict. The reader plays the roles of the Doctor, Peri, and Harry Sullivan, and works to put history back on course and ensure a victory for the North. Very cool stuff.

So I did a lot of reading as a kid, and a lot of writing, which led me, essentially to where I am today. A writer who tries to read as much as he can, despite his really busy schedule.

So how did I get into reading? I had a mother who read in front of me regularly, leading by example. She encouraged me when she saw me reading. My teachers assigned me fun and exciting books. I saw movies based on classic books on Masterpiece Theater and I had a hunger to read the originals. I had friends in school who read. It all added up.

But I think I owe most of it from watching my mom reading on the couch. It is a great image I will always remember.